Thwack!

Ballet slapped the black girl in the face and destined her for greatness.

*

Mabinty Bangura was born in Sierra Leone with spots all over her body. Her parents had loved her very much, but after they died, she turned into a war orphan. One day, Mabinty slipped out of the orphanage into the Harmattan wind. Keening towards calling, she pressed her face up against the wrought-iron gate. Suddenly, a magazine filled with white people hit her smack in the face. “Ugh! Trash!” I exclaimed. But it wasn’t trash at all. I had been attacked by the pages of a magazine.” Mabinty had never seen white people before. “The magazine was stuck in the gate, exactly where my face had been. I reached my hand through and grabbed it.” On the cover, a white woman wore a short, pink skirt and shiny, pink shoes. How strange and magical! Might she be dancing? “Someday I will dance on my toes like this lady. I will be happy too!”

Mabinty tore off the cover and hid it in her underwear. This became her secret treasure. Later, she showed the picture to her new American mother. Before she could even speak English, Mabinty wanted those pink shoes. Like a sugar plum fairy, her new mother granted her wish. Mabinty got to take ballet! She wore leotards and tutus and pinned her hair into a bun. She grew up nourished and safe in a loving (white) family. She became American. She became Michaela DePrince. She became a ballerina.

*

How do we tell stories about black girls and ballet?

How do ballet stories tell black girls how to be?

*

As a black girl in Detroit in the 1980s, I didn’t read Michaela DePrince’s Taking Flight. It didn’t yet exist. In fact, no books existed about a black girl ballerina, or at least none that I ever saw. Back then, I couldn’t have named even one black ballerina, black bodies in white boxes.

[ Janet Collins.

Joan Meyers Brown.

Raven Wilkinson.

Judith Jamison.

Debra Austin.

Anne Benna Sims.

Llanchie Stevenson.

Lauren Anderson.

Misty Copeland.

the incomparable

Katherine Dunham

who some people say isn’t technically a ballerina,

but she trained in ballet and is such a force

of nature, in dance, you have to say her name! ]

Despite the fact that none of the ballerinas looked like me, I devoured ballet stories. Ballet for Laura. Laura’s Summer Ballet. As the Waltz Was Ending. Ballet Shoes. This funny habit of reading ballet has spanned my entire life. Girl in Motion. Bunheads. Astonish Me. Holding onto the Air. Dancing in the Wings. Firebird. The Cranes Dance. Pointe. Dancing Shoes. Winter Season. The Sleeping Beauty. Balanchine and the Lost Muse. The Walls Around Us. Vanishing Rooms. Breaking Pointe. Life in Motion: An Unlikely Ballerina. Fiction and memoir, this list doesn’t even count movies and TV. The Red Shoes. The Turning Point. A Ballerina’s Tale. (Go Misty!) Black Swan. Dancer. First Position. Center Stage. Dance Academy. Even Flesh and Bone, that grim ballet series I binged after my hysterectomy . . .

Despite the fact that I never received serious training; despite the fact that I never saw even one live ballet as a girl; despite my recognition that this form of dance defines itself completely against me—my dark skin, my flat feet, my round belly, my wide hips, my nappy hair, my big ass, and, most of all, my insurgent black feminist performance art practice—ballet somehow remains bedrock to my sense of art, dance, and self. Despite or perhaps because.

*

“Who’s there, when the black body has been interrogated, tried, and convicted on the basis of a white aesthetic? . . . At the equator of our race consciousness, who’s there?”

– Dr. Brenda Dixon-Gottschild, The Black Dancing Body

*

Anna Linado, a white, teenage girl from Rock Island, Illinois, is completely devoted to ballet. Quiet and shy, she has dark hair and impressive arches in her feet. Like all ballet heroines, she is more beautiful and talented than she realizes. She isn’t rich, but her middle-class family sacrifices for her training. After receiving a prestigious internship to a ballet school in New York City, Anna must prove herself to her ballet teachers to continue a life of dancing. Her dream is a job offer from the school’s professional ballet company. Nicole, a mean girl, blonde and rich, is jealous of her talent and tries to jeopardize her future. Tyler, the most talented boy dancer in her class, adds a dash of romance. Only there to keep things heteronormative, Tyler is really beside the point/e. Anna loves dancing more than anything else.

A complete innocent at seventeen, she’s never even been kissed. Anna never masturbates, never craves good sex, never feels the guilt of doing it in the back of a car, never suffers the humiliation of sexual neglect, the shame of STIs, or the absolute catastrophe of teenage pregnancy. In Detroit, in the 1980s, I was told that getting pregnant would ruin my life. These things can happen to teenage ballerinas. (I saw Fame!) However, in this book, ballet is her lover, her baby, her baby mama and daddy, her contraception and immaculate conception. Her body, her desire, are under complete control, for use only for creative expression. To me, a dreamy black girl going to a predominantly white, Catholic school, this situation seemed like heaven.

High minded, the ballet book girl is competitive and tough. Underneath her pink skirt and shiny pink shoes, her ribs jut forth; her toes blister and bleed. Her anxiety about her success marks her modesty, her ambition and perfectionism. “I’ll die if I don’t get into Ballet New York. Die!” In The New York Times, on June 26, 1987, Isabel Wilkerson writes “in Detroit, nearly 21 of every 1,000 babies dies in the first year of life. This is the second-highest infant mortality rate in the country.” Describing Hutzel hospital where my sister later had weekly lectures in medical school on obstetrics, Wilkerson reports: “Last December, a 13-year old girl showed up pregnant. She had no prenatal care and gave birth to a boy weighing 1 pound, 4 ounces.” Although never named, we know this nameless girl is black. In June 1987, I was almost thirteen years old. The romance, tortured and full of suspense, is always between the (black) girl and her future. Will Anna get a plum role in the student workshop production? Will she get a chance to start her dancing career? Of course, she will. Girl in Motion follows the script. The ballet girl may look like a princess, but she operates like a machine. Dancing is her life.

*

On the panel in Iceland, Elizabeth Kendall’s eyes welled up with tears. A dancer and deep writer about ballet, she’s been describing the passion of young girls for dance. Afterwards, I talked to her and Margo Jefferson, another amazing writer, about the impact of ballet books in my girlhood. “Wow, I thought at first you were just being nice to me,” Elizabeth said, “but I can see how much you care.” Indeed. Despite the capitulation to white male authority and patriarchal ideals, the constant hunger, the need for approval, the anxiety about height, weight, excessive flesh, the hyper-femininity, the suffering in silence, the heroines in these books forged me. Despite or perhaps because.

Girls in ballet books/ ballet book girls are glamorous and diligent, glamorous in their diligence. Young, serious, disciplined, ambitious, and indomitable: they epitomized the artist as a girl. This is who I wanted to be. This was the only place I saw her. The girls in the ballet books never saw me. Margo commiserated: “What does it mean to dream of something that doesn’t dream of you?” So what if the ballet book girl was thin, white, and not from Detroit? Those weren’t the parts I wanted to emulate. Before I could even articulate it, I wanted those pink shoes. Trajectory, tenacity, and talent.

*

A couple blocks away from my house, on Livernois, the erstwhile Avenue of Fashion, stood a storefront dance studio. It’s not there anymore, and I don’t remember the name, but for a short while it was where I took ballet. The teacher was black, and I can’t really remember her name either, although thinking of her makes me feel warm inside. My story goes that she had danced in Chicago and New York and then come back home to Detroit to start her own school, so kids could learn to dance. Everyone was black, with the exception of this white girl named Amy who claimed a black girl in class was her foster sister. I never knew if they were joking . . . The vibe overall was playful and pleasant, as we learned ballet, tap, and gymnastics. I think I liked it. I don’t think I was very good. For some reason, my memory is hazy, not sharp like my recall of Laura’s Summer Ballet or Dancing Shoes, which is still my favorite.

*

Rachel and Hilary aren’t blood sisters although it doesn’t matter to them. This black girl named Octavia loaned me Dancing Shoes on the last day of fourth grade. This was the end of my first year at Shrine of the Little Flower, a predominantly white, Catholic school outside of Detroit. We didn’t live close by or go to each other’s houses, so I got to keep the book the entire summer. Before their mother died, a lady came to the house in Folkestone to say that Hilary was a natural. The family was poor—before the book began, the movie star father had died in a plane crash without saving any money—but Hilary and Rachel’s mother still managed to put aside a little each week for Hilary’s ballet lessons. (One summer in New York, as a broke graduate student, I bought this book and read the whole thing again in sunny Prospect Park in one afternoon and then promptly returned it the store.) Ballet cost but was real dancing. So even though Hilary was lazy and funny and liked to turn cartwheels and walk on her hands and didn’t really care about ballet, Rachel was convinced she had to do it. Why else had their mother sacrificed so much?

“Rachel, her eyes on the stage, was just about to slide off into another daydream when the Fairy Queen began to dance to Tschaikovsky’s Sugar-Plum Fairy music.” Quiet and serious, her nose always in books, she had her own nascent dreams of the stage. “The Fairy Queen put an arm around Rachel. ‘You have a dancer’s face. Can you dance?’” Rachel had become a Wonder, but that didn’t count. “Rachel pointed to Hilary. ‘No. She can.’ Rachel’s whisper was more fierce than she knew. ‘She’s to go to The Royal Ballet School and be a proper dancer like you.’” Before she could even speak up for herself, she wanted those pink shoes. “Like Me!” The Fairy Queen looked half sad, half amused. “I’m afraid that won’t do her any good . . .”

(What do you do when your dream doesn’t dream of you?) “Rachel watched the Fairy Queen rise on her pointes, lift her arms, and glide onto the stage. At that moment, though she did not know it, the first tiny seed of doubt about Hilary’s future was sown in Rachel’s mind.” The real twist is that neither Hilary nor Dulcie, their spoiled cousin, the best dancer in the school, end up as ballet stars. Despised, discounted Rachel gets discovered by a movie director and becomes the lead in a motion picture. After starting with ballet, it moved in a different direction.

*

At the studio in Detroit, I was finally doing ballet, or was starting to learn how to do it. As has happened so often in my life, reality differed somewhat from my reading. We did not live together in the school or form a troupe of talented moppets. No former principal dancer named Madame presided over class. No accented, white man served as mercurial artistic director. No portly Russian accompanist played piano (we had no live music at all). No one smoked. No one sewed, slammed, or burned any toe shoes. No mothers meddled and tried to live vicariously through us (they were just nice enough to drive us and maybe wait around). No one cut themselves or starved (at least that I could see, young and absorbed in just trying to follow the steps).

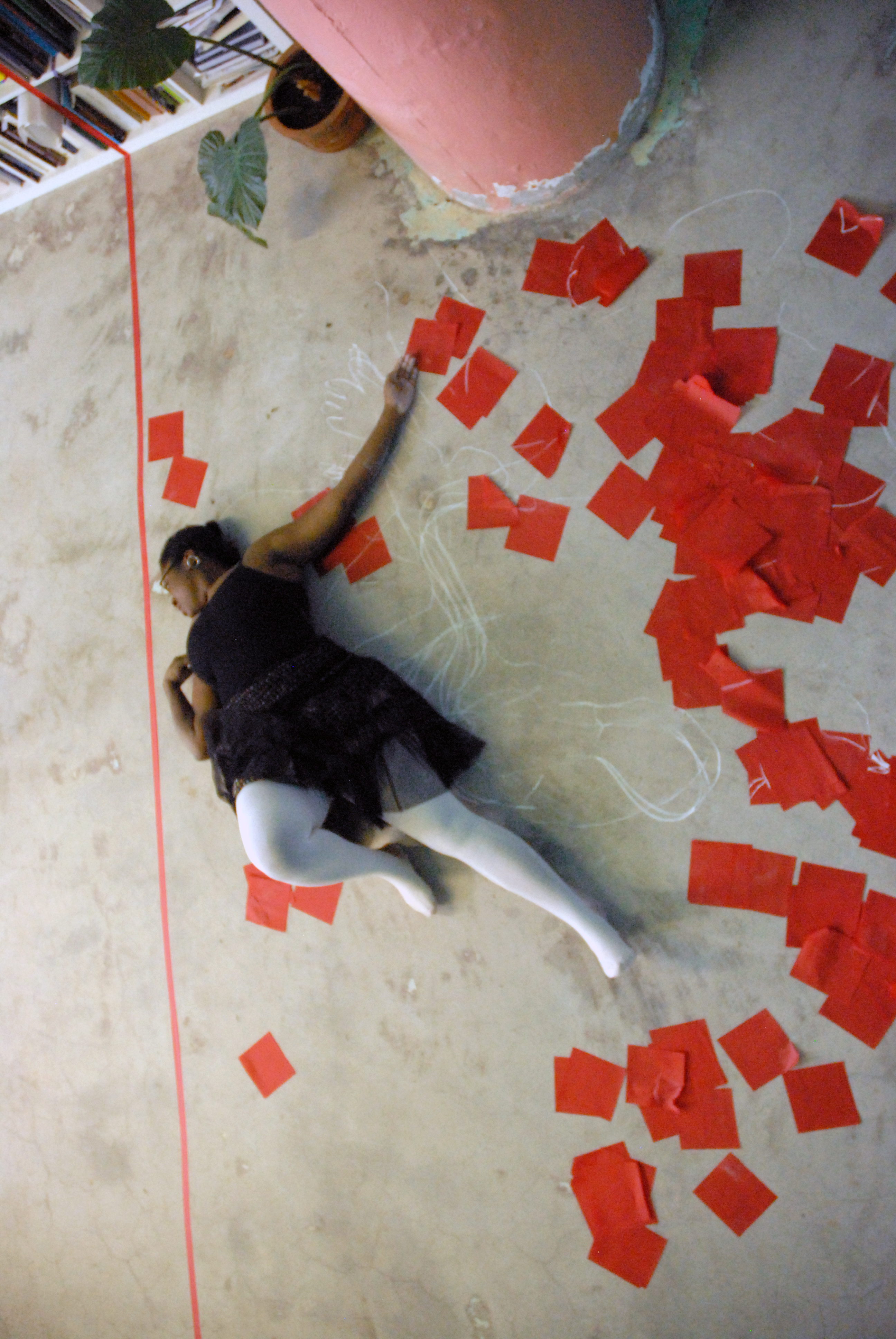

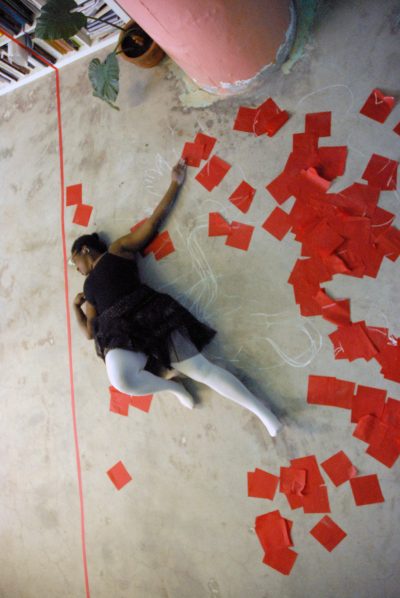

No one lifted ballet up as better, told us that we had to or couldn’t do it. This ballet was no drama. No glamour. No whiteness. No sweat. Well, maybe sweat. Huffing and puffing and shuffling across the floor. We were black kids dancing! Living the dream! Trying to leap and have some fun. I was finally fulfilling my class aspirations. Plié. Relevé. Chassé. I was fleshing out words found in every ballet book, assuming the five basic positions. In ballet classes in Minneapolis and Mexico City, I have assumed these same positions. Often, I find myself the darkest, fattest one in the room. I turn up. I turn out. I point my foot and tendu. The black swan claims her place.

*

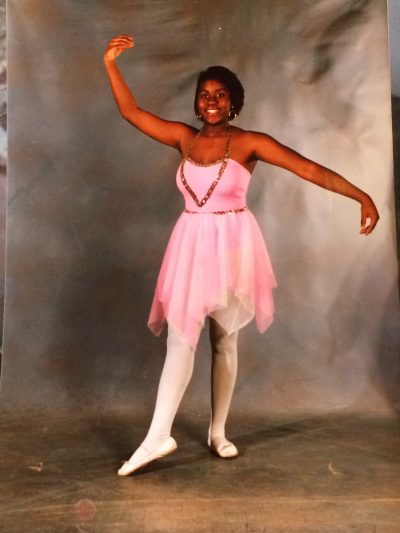

In the Detroit recital, our teacher placed me dead center on stage in the ballet routine. Was this due to some magnetism or talent? Was this even true? Has my memory failed? I have no idea. In my recital costume, I am brown and plump, more beautiful than I realized. I love the picture of me in my bright pink skirt, and light pink shoes. It’s the only evidence that I ever did ballet. The audience bobbed their heads to the tap. They hooted and hollered for the gymnastics. Their appreciation of the ballet was more quiet and polite. Suddenly, in the middle of the dance, the conformity of our bodies freaked me out. What would happen, I thought, if I just didn’t do the step? How would I feel? Shameful or subversive? Could I survive it? Would anyone be able to tell? It was my dream to take ballet and dance in a recital. There I was on stage and, for some reason, just for a moment— a tiny seed—I wanted to do something different. So I did.

*

As a black feminist performance artist, I have a complicated relationship to dance. I do it, make it, use it, watch it, pursue and consume it. I seek it out, feel rejected, and return to it again. Most often, I disclaim it. Or at least myself in it. “Well, I’m not really a dancer,” I say, while dancing in performances around the world. Ballet books taught me that dancers have impeccable training, technique, and perfect bodies. (White) dancers are long and lean, willowy, elegant and graceful. (Black) dancers, when they are allowed to exist on stage, are strong, compact, rhythmic, and athletic. In her brilliant cartography The Dancing Black Body, Brenda Dixon Gottschild explodes these stereotypes, body part by part. Feet. Butt. Skin/ Hair. She exposes the undermining of (black) potential as well as a rich, resistant history of black dance in many forms.

Her interviews with dancers are especially telling. Bill T. Jones states: “a black dance is any dance that a person who is black happens to make.” Marlies Yearby says: “on some level, all of it is black dance because you know, when you look at the history of ballet, its rhythms were drawn from Africa . . .” Brenda Bufalino declares: “When I saw a contraction, I almost fainted from ecstasy! [I learned] this wonderful animal-like quality . . . And I definitely do associate it with black dance. . . Not European . . . When I saw that, I didn’t see it separate from my white body. I saw it as . . . a symbiosis of ‘Oh! That’s also me!’” Both Gottschild and I have some questions about this “animal-like quality” and its association with blackness. (Really? Did white people never evolve?) Still, this feeling of symbiosis resonates. How else to explain my connection to ballet, my fascination with ballet stories? Cognitive dissonance? Delusion? Disidentification? Imagination? Or sheer, stubborn will?

*

A few years ago, I collaborated with performer Moe Lionel on [ ] doesn’t known [ ] own beauty, a performance art work based on Melvin Dixon’s []Vanishing Rooms[/]. In this 1991 novel two black dancers, Ruella and Jesse, negotiate the aftermath of a tragic hate crime, the sexual assault and murder of Metro, Jesse’s white gay male lover. In our performance, we explored race, violence, submerged history, and desire along with the nature of our own interracial, sexually blurred love affair. We read sections of Dixon’s novel to each other live on stage. We played hangman, moved and stretched like dancers. After dancing to Janet Jackson, we activated Nina Simone’s classic song “She Doesn’t Know Her Own Beauty.” We followed the novel’s footsteps.

My specific gestures in this work embody my history with ballet stories. Ruella says: “My memories were ballerinas gliding in and out on point.” I don flesh colored tights, pin my hair up into a nappy bun, and become the ballet dancer. I wear my glasses and read from a book where a black girl makes dances and claims artistic power. She lives in a hard city. She wants her loved ones to live. She wants to live fully herself. “Dancing solo requires your own motion. You follow your own lead . . . Where was I leading myself?” I wanted to take ballet, stand center stage, and do something else. “I hate walls. I hate ceilings . . . and metal gates . . . hold you hostage inside.” I think of Mabinty / Michaela and her magazine cover at the gate. I think of the nameless black girl in Detroit and her baby. Did they make it? Michaela de Prince made it, dancing, living her dream, living my dream too. I think of myself making it up: my reading, a germination, my dream, not to become a ballerina, but something beyond words. A black woman artist. A black swan. In symbiosis, transposition. “I want to be in air. Make a space out of movement. A space I can break if I want.”

About the Author: Gabrielle Civil

About the Editors: Thomas F. DeFrantz, Eva Yaa Asantewaa

Wenger-Landis, Miriam. Girl in Motion. [on-line]: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2010. Print.Streatfeild, Noel. Dancing Shoes. New York, NY: Yearling, 1957. Print.Wilkerson, Isabel. "Infant Mortality: Frightful Odds in Inner City." The New York Times, 1 Jun 1987: Special. Print.Dixon-Gottschild, Brenda. The Black Dancing Body: A Geography from Coon to Cool. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005. Print.DePrince, Michaela, and Elaine DePrince. Taking Flight. New York, NY: Ember / Penguin Random House, 2016. Print.